It’s the foams specifically for fighting fuel fires that are made from PFAS. Unfortunately, their safety gear also is loaded with PFAS.

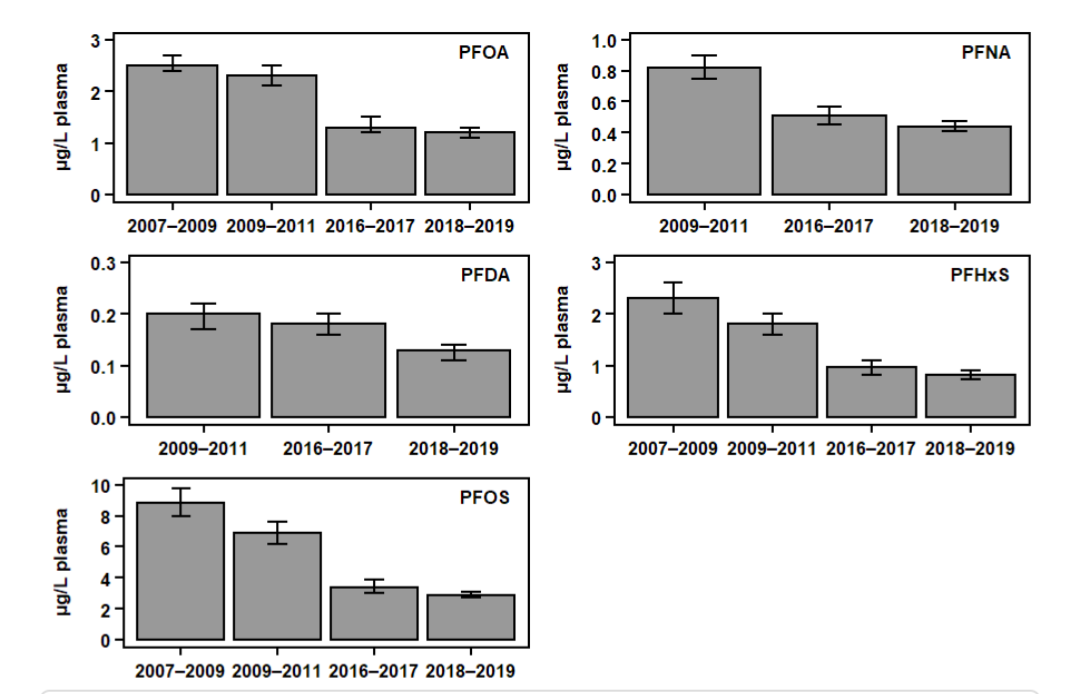

Blood serum PFAS concentrations thankfully have been decreasing over time. It’s probably not worth getting yours tested unless you had some specific exposure other than consumer goods. You should ask your doctor, if you have one.

This data is from Canada, but the results are similar for the US.

Unfortunately, even if we stopped using PFAS entirely it will remain a legacy problem in wastewater and landfills because so many consumer products contain PFAS. That said, some places are working towards banning PFAS in new products and some of the really nasty ones are already banned in many countries. Here is Canada’s plan to phase PFAS out of industrial and consumer goods:

For simplicity, this process is called clarification.

Unfortunately, coagulants are not effective at removing PFAS. The only effective methods for PFAS removal are adsorption (using granular activated carbon or ion exchange resins) or reverse osmosis filtration. These approaches are not used in traditional wastewater treatment because they are very expensive and are not required to meet registrations. However, potable reuse facilities will use these approaches to further treat wastewater effluent to drinking water standards. This is the future of water supply for arid areas like the southwest USA.

Also PS, the most commonly used coagulants are aluminum sulphate (alum) and ferric sulphate, which are not polymers. Polymers definitely are used (especially where I live) but they are more expensive and thus avoided when not needed.

It was the triple alliance, also called the Tenochca Empire.

If you want to learn more about pre-contact Americas and the impact of the Columbia exchange, please read the book 1492.

R with the tidyverse package is amazing once you get over the learning curve. It’s so much easier to simply type a few lines of code then to fiddle with the Excel GUI, plus the ability to customize the plot is much, much better in R.

Yes making a simple plot in Excel is relatively easy, but try making something evening remotely complex and it’s terrible. A box plot is a great example of this, 2 lines of plotting code in R for a basic plot but an absolute nightmare to create in Excel.

As stated in the article, this isn’t a big problem for communities with centralized water treatment systems, rather for individual homes drinking well water which is contaminated by agriculture.

In a municipal treatment plant you have a few options for removing nitrates including reverse osmosis (membrane filters with very small pores, allowing them to reject very small molecules), ion exchange (swap nitrate with another, less harmful ion), or biological treatment (use microorganisms to turn nitrate into nitrogen gas).

In your home, reverse osmosis is really the only feasible option, which can be expensive to install and costly to maintain. Ideally, some sort of tax on fertilizer would be used to pay for these in house treatments, but that would increase the cost of food.

The US is a massive country friend, there are lots of places with combined sewers (domestic wastewater and stormwater) that will bypass treatment when there is a big rain event, especially in coastal cities that discharge wastewater to the ocean. It’s not ideal but the alternative is massively oversized treatment plants or replacing all of the existing sewer infrastructure to separate the sewers. Both options would cost tens of billions of dollars in any of the large east coast cities. People are not willing to pay for that.

There are varying levels of Aphantasia, for my partner it is complete but for you if may only be partial. The wiki page I linked discussed it a bit.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aphantasia

My partner has Aphantasia. Brains are strange! She cannot visualize in her mind which makes it very challenging to do certain tasks and many things she does are based on muscle memory. Also interestingly when a song gets stuck in her head it is like she is making all of the sounds with her inner voice. For me, I can hear the song like there is a recording playing in my head.

Sadly this is pretty common. Here are some nasty pictures from a recent one in greater Vancouver.

I’m a water engineer with a PhD, so not a tech nerd but definitely a nerd :) I came here mostly because I find the Reddit app annoying and the app I was using came here.

The Romans used lead as a sweetener…

I don’t know the details about alum production (assuming that is what you are referring to), but there are many alternative coagulants available now. Sure the supply logistics would be incredibly challenging and many people would have to boil their water or use point-of-use filters, but this take is pretty doomer in my opinion. Most plants use alum because it’s cheap and easy, not because it’s their only option.

Systems that were already using activated carbon or ion exchange for organics removal may have some treatment capacity, but otherwise the first systems specifically for treating drinking water are being designed and constructed now. There are contaminated sites that already have treatment or containment in place.

This is very interesting. Currently, most ion exchange systems that remove PFAS have to dispose of their brine as hazardous waste, which is very costly and doesn’t necessarily destroy PFAS - in Florida, for example, they inject the brine into a deep aquifer.

A lot of novel technologies target PFAS destruction in these concentrated waste streams, but often further concentration is required before you can effectively destroy PFAS with advanced oxidation processes. If they could use low-UV to destroy it without further concentration or additional chemicals (beside the salt already used to regenerate the resin), ion exchange would become a much better solution for treated PFAS contaminated water.

It’s “forever” in the environmental sense that they don’t break down naturally (or at least very, very slowly). That said, “forever chemicals” is more of a media buzzword than a term that scientists use.

Exactly my workflow, but I used R Markdown!